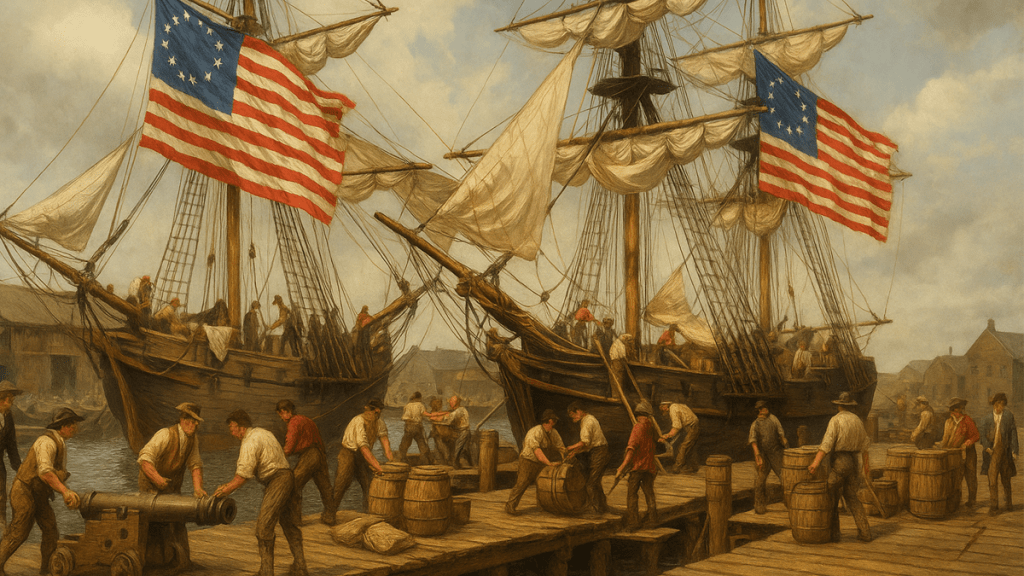

By October 9, 1775, the Revolution had been fought on farms and hillsides, in taverns and town squares, but never yet on the open water. That changed when the Continental Congress voted to arm two ships and send them against British supply vessels. With that single decision, America began the long, uncertain process of becoming a naval power.

John Adams had been calling for this moment for months. He argued that the colonies could not defend their liberty if they could not defend their coasts. The British Navy ruled every harbor from Boston to Charleston. It controlled trade, enforced blockades, and starved the rebellion of powder and supplies. Adams believed that even a small fleet could harass British shipping, seize valuable cargo, and give the colonies a fighting chance. On October 9, Congress finally agreed.

The order was modest. Two ships were to be fitted out and armed, tasked with intercepting British transports carrying military stores to America. It did not sound like much, but it was the first spark of what would become the Continental Navy.

From that decision came a new sense of identity. For the first time, Americans were not just resisting; they were preparing to fight on equal terms. The sea had always been New England’s lifeblood, and now it would become the Revolution’s weapon.

In Philadelphia, Adams and his colleagues debated how to fund and crew this new fleet. In Cambridge, General Washington was already experimenting with small armed schooners along the Massachusetts coast, authorizing raids on British transports. The colonies were learning that liberty could not simply hide behind walls or hills. It had to move, strike, and survive on the waves.

This week’s episode of Revolutionary Talk explores that turning point. The host reminds listeners that this was more than a strategic move. It was a declaration of will. A people who take to the sea declare that they intend not just to defend themselves, but to reach beyond their shores.

The ships that followed were not mighty warships of the line, but converted merchantmen, brigs, and schooners. Their captains were fishermen, traders, and privateers. They carried the same courage that had faced British regulars at Lexington and Bunker Hill, only now it would meet the enemy on the water.

Here in Norwich, the news carried a special resonance. The Thames River and nearby shipyards were already part of the region’s maritime trade. Local sailors and merchants had long experience with the sea, and many would soon find themselves part of this grand experiment in naval defiance. In the taverns, talk turned from inflation and betrayal to opportunity. Letters of marque would soon allow private ships to seize enemy cargo legally, and for once, profit and patriotism would sail under the same flag.

In London, the news was met with ridicule and alarm. Ministers laughed at the idea of an American navy, but the Admiralty quietly drew up new orders for a tighter blockade of colonial ports. The King’s speech to Parliament was already being sharpened. His words would soon brand the colonies in open rebellion.

The Revolution had reached the sea, and there would be no turning back.

From Philadelphia’s parchment to Norwich’s wharves, liberty had found a new wind. The fleet was small, its men untested, and its mission uncertain. But as the host declares, “Every great nation begins somewhere, and ours began with two ships and an idea too strong to sink.”

Leave a comment