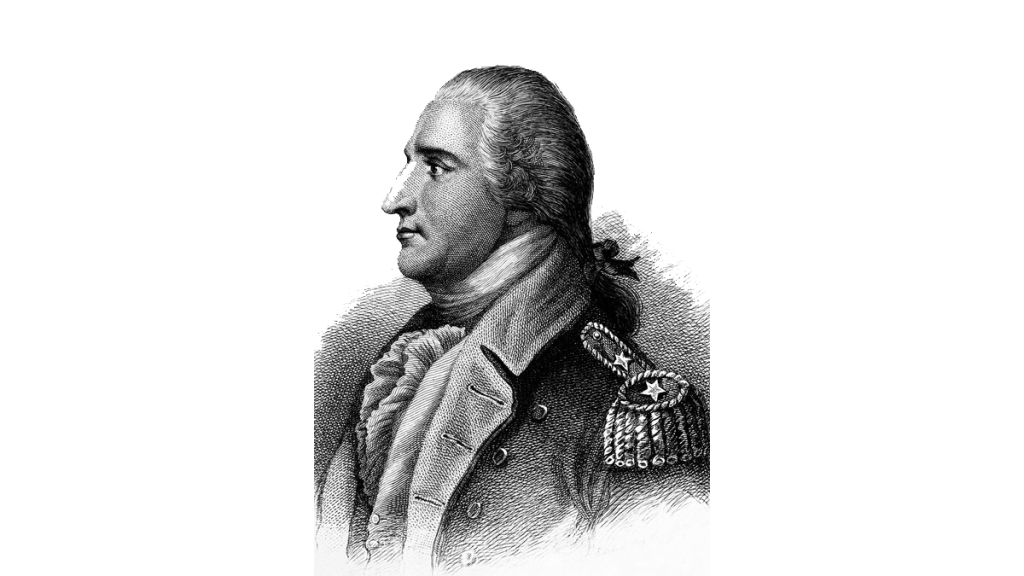

On October 3, 1775, Benedict Arnold was not a traitor. He was not the man whose name would later be cursed in every corner of America. On this day, the Norwich born hero, perhaps the boldest of the Revolution, was leading men north into the Maine wilderness with a vision so daring that most in Congress thought it was madness. To understand Arnold on this day is to see him as his men saw him, as Washington saw him, and as the Revolution desperately needed him to be.

Arnold’s service had begun at the very opening of the war. When the first shots were fired in April, he was already in motion, planning a blow against Britain’s northern stronghold. In May, only weeks after Lexington and Concord, he helped lead the raid on Fort Ticonderoga. The capture of that fort and its cannon gave Washington the artillery that would one day drive the British out of Boston. Arnold had seen the need, raised men largely at his own expense, and risked his life to seize those guns. Yet when the news reached Congress, it was Ethan Allen who received the credit. Arnold was largely overlooked. Worse still, Congress hesitated to reimburse him for the costs he had shouldered, muttered about his ambition, and passed over his requests for promotion.

This mistreatment stung. Arnold was a man of pride and a man of temper, and Congress’s suspicion cut deeply. Many men in his place might have walked away. But Arnold was not one to shrink from a fight. Instead he pressed harder, determined to prove himself again.

The man who needed him most was General George Washington. By late summer of 1775 Washington commanded the Continental Army outside Boston. His army had the British trapped in the city but could do little more than sit and wait. Washington’s men had perhaps nine rounds of powder each. They lacked supplies, discipline, and training. They could not storm Boston. They could not break the siege. Washington was desperate for options.

Arnold came to Cambridge with one. He proposed marching north through the Maine wilderness to strike at Quebec. To many, this looked insane. The maps were old and inaccurate. The rivers were treacherous. The route was nearly impossible. Yet Arnold argued that Quebec was the key. If it could be taken, Canada might rally to the American side. Britain’s northern flank would collapse, and the Canadians might open their granaries, their ports, and their powder stores. For an army starving for supplies and for a cause in need of bold victories, Quebec offered everything.

Washington was not a reckless man. His instinct was always caution, his preference always for entrenchment over gamble. But he recognized in Arnold a rare quality. Arnold was fearless, energetic, and resourceful. Washington saw in him a sword-arm to balance his own steady hand. He approved the plan and gave Arnold command of about 1,100 men. It was a bold gamble, perhaps reckless, but Washington knew boldness was sometimes the only weapon left.

The expedition set out from Cambridge in mid September, marched to Newburyport, and sailed to the mouth of the Kennebec River. By the last week of the month they were at Fort Western, building and loading bateaux, the flat-bottomed boats that would carry them north. The boats were poorly built, leaky and fragile, but on October 3 they pushed forward into the wilderness.

The men were still full of optimism. They believed Quebec was only weeks away. They imagined a smooth passage upriver, a quick strike at the city, and a warm welcome from the Canadians. They had not yet discovered that their maps were lies, their provisions would soon spoil, and their journey would stretch into misery. For now they sang as they rowed, joked about their victory to come, and trusted Arnold to lead them.

Arnold was everywhere. He was not the sort of commander who stayed dry while his men struggled. He shoved at the bateaux, cursed at the leaks, shouted at lagging officers, and encouraged the weary. He shared their food, their burdens, their hardship. The men knew his temper, but they also knew his courage. They believed he would not ask of them what he would not endure himself. That counted for much in the wilderness.

While Arnold drove his men north, Congress in Philadelphia dithered. John Dickinson and others fretted about cost and provocation. They pinched pennies and weighed risks while Britain sent regiments and ships. Congress treated Arnold as a nuisance, questioning his accounts and denying him honors. Yet Arnold pressed on anyway, giving his money, his energy, and his life to the cause. It is not hard to see in hindsight how such neglect planted the seeds of future bitterness.

Across the ocean, King George III and his ministers were preparing a different kind of declaration. In London the King’s speech branding the colonies in “open and avowed rebellion” was being drafted. Ministers discussed reinforcements and convoys. German princes were bargaining to send Hessian mercenaries. Britain’s leaders believed rebellion could be crushed with money, ships, and regiments. They counted contracts and battalions, certain that the empire’s weight would smother the uprising.

Contrast that with Arnold on the Kennebec. Britain had fleets and mercenaries. America had leaky boats, spoiled rations, and a commander with sheer determination. It is worth asking which force history truly feared.

The stakes could not have been higher. Quebec was not just a city on a map. It was the key to Canada, and Canada was the key to the north. If Quebec could be taken, Britain’s stronghold would collapse, and the Americans would have allies, supplies, and new ground to stand upon. If Arnold failed, the expedition would be remembered as folly, and the cost in lives would be enormous. But the attempt itself showed a truth that even Congress had not yet grasped. The Revolution could not be won by defense alone. Boldness was required.

So mark the day. On October 3, 1775, Benedict Arnold was not yet a traitor. He was a hero, wronged by Congress, trusted by Washington, admired by his men. He was beginning one of the most daring marches in American history. He believed Quebec could fall, that Canada could join the cause, that boldness could turn the tide. Washington believed in him. His men believed in him. And the Revolution needed him.

It is easy to remember Arnold only for treason. But if you stood on the banks of the Kennebec on October 3, 1775, and saw him driving his men forward through mud and rain toward a prize that might change everything, you would have seen him as they did. A leader. A fighter. A hero in the making.

Leave a comment