October 1, 1775 – Powder and Parliament

The Revolution looked like it was winning in the early autumn of 1775. From the hills around Boston, you could see the American camps strung out in a ragged cordon around the city. The British garrison under General William Howe was still bottled up after the bloody fight at Bunker Hill. American flags flew over crude redoubts, militiamen drilled in fields that only months before had been pastures, and sentries kept watch on the city as though victory was only a matter of patience. To anyone peering down from a hillside, it seemed the Patriots had seized the upper hand.

Appearances deceive.

On October 1, 1775, General George Washington sat down to write Congress, and the words he put on paper shattered any illusion of security. His army, he explained, was running out of the very thing an army cannot do without: gunpowder. Washington estimated that his entire force had barely enough to fire nine rounds per man. A battle, perhaps even a skirmish of serious weight, could drain their stores and leave the army defenseless. The siege of Boston was not a stranglehold. It was a bluff.

The Siege From Afar

The siege had begun in April, after the British retreated into Boston from the running fight at Lexington and Concord. By summer, thousands of militia had come down from New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Rhode Island, joined by men from Massachusetts itself. They threw up earthworks, blockaded the land routes into the city, and dared the redcoats to come out. In June, at Breed’s Hill, they showed they could bloody the King’s army, killing or wounding more than a thousand men before their powder gave out. The British held the field, but the cost of victory kept them penned in.

By October, life in the American camps had settled into a grueling routine. The men built huts, dug trenches, and stood watch. They scrounged for food in a countryside already strained by the presence of so many mouths to feed. The weather began to turn, cold rain soaking clothes and boots, mud seeping into tents. Morale wavered. Desertion ticked upward. Some men’s enlistments were coming due in December, and Washington knew many would not sign again. He faced the possibility of an army evaporating before his eyes when the year turned.

Yet none of this was as frightening as the powder situation.

Washington’s Powder Panic

The general’s letter of October 1 was frank in a way Washington rarely allowed himself to be. He usually cloaked his language in the formal style of command, reporting difficulties while projecting confidence. But the shortage of powder was too dire. He told Congress plainly that his men had so little powder it was “alarming.” If the British sallied out, his defenses might collapse after a single volley.

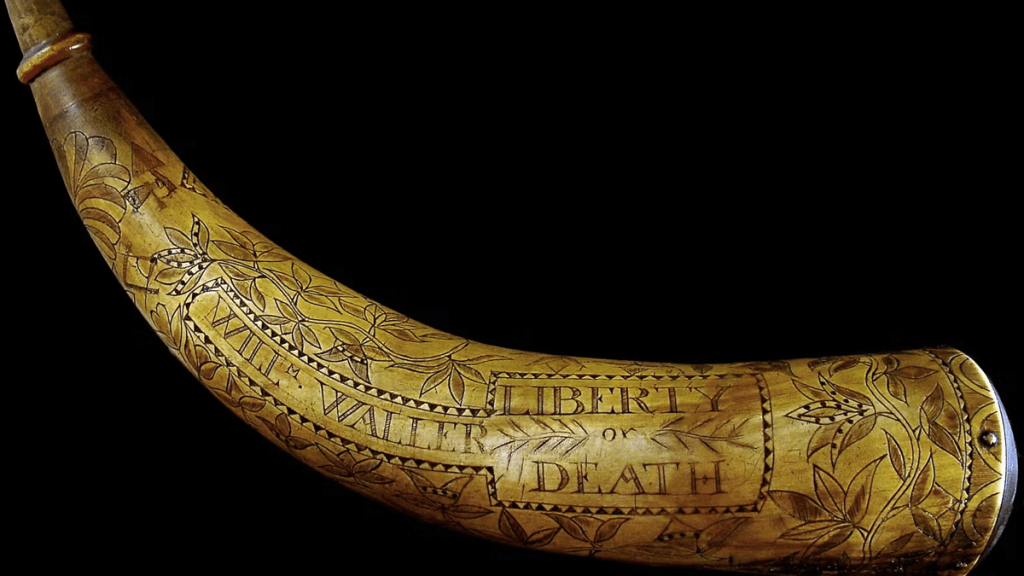

Washington concealed this truth from his soldiers. The knowledge could unravel the army. He issued orders that no musket should be discharged unnecessarily, not even for hunting or training. Drills were conducted with empty barrels. Powder horns were to be guarded like treasure. Every keg in storage was counted, inventoried, guarded by sentries. Even his officers were not told the full scope of the shortage. To them, he implied there was enough, so long as they enforced his rules.

In private, Washington was furious. He had inherited the army from New England officers who had been eager to surround Boston but lax in supply. He wrote that he found “a mixed multitude of people under very little discipline, order, or government.” Powder had been wasted in constant, unnecessary firing. Discipline had been lacking. Now he had to fix it with almost nothing in the magazines.

The irony was cruel. The Revolution had begun with shots fired in April, had shaken the Empire with volleys at Bunker Hill, and now risked ending not in a climactic defeat but in the quiet suffocation of empty powder horns. Washington knew his army could hold its lines, build its works, even look formidable. But without powder, it was all theater.

Congress in Limbo

Congress in Philadelphia received Washington’s October 1 letter and did what Congress often did: it debated. Delegates were pulled between two visions. John Adams and the New Englanders pressed for full commitment to war. Adams argued that powder and arms must be bought, manufactured, and seized wherever possible. He pushed for a navy to harass British supply lines, for privateers to be loosed on the seas, for every colony to mobilize.

But John Dickinson and his allies urged caution. They still spoke of reconciliation. To them, Washington’s plea for powder was alarming, but so too was the idea of supplying an army that might one day march not in defense but toward outright independence. Dickinson drafted petitions to the King, urging redress, not separation. Even as muskets cracked around Boston, Congress clung to the hope that this war was not truly a war but a dispute that might still be settled.

So October 1 became another day of hesitation in Philadelphia. Congress promised to seek powder, but it had no real network to buy or transport it. It had no navy to bring supplies past British blockades. It relied on smugglers, on merchants sympathetic to the cause, on French powder sneaked through neutral ports. Washington’s warning underscored the fragility of it all.

England’s October

Three thousand miles away, October 1775 looked very different. In London, Parliament was preparing to open its new session. George III and his ministers finalized the King’s Speech that would be delivered to the Lords and Commons. Its central message was clear: the colonies were in “open and avowed rebellion.” No more talk of wayward subjects. No more patience for petitions. This was treason, and it must be treated as such.

The King’s position had hardened through the summer. He had written to Lord North in August that “blows must decide” whether the Americans were subjects or rebels. By October, he intended to say it publicly. The draft speech circulated among ministers. The language was uncompromising. Parliament would be asked to fund more troops, expand the navy, and consider alliances to reinforce the British army in America.

One of the most controversial issues was the use of German auxiliaries. Negotiations were underway with the Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel and other princes to hire soldiers — what Americans would later call Hessians. Word of these negotiations was already leaking in London. Pamphleteers attacked the idea of unleashing foreigners against Englishmen in America. Merchants worried that escalating the conflict would destroy trade with the colonies. But supporters of the Crown saw it as necessary: the rebellion could not be contained with the troops on hand. More men were needed, and quickly.

In coffeehouses, the debate was fierce. Some Londoners sympathized with the colonies, arguing that Parliament’s taxes and heavy hand had provoked the crisis. Others demanded firmness, insisting that the colonies must be reminded who ruled the Empire. By October 1, the balance of power was already tilting toward repression. When Parliament reconvened later that month, the King’s speech would confirm what Washington suspected: Britain no longer considered the colonies petitioners but enemies.

The Meaning of the Day

The juxtaposition is striking. In Boston, Washington’s army looked bold but was running out of powder. In Philadelphia, Congress looked united but remained divided over war and peace. In London, the Crown looked invincible but was anxious about manpower and money. All sides were weaker and stronger than they appeared.

October 1, 1775 was not a day of cannon fire or bloodshed. It was a day of paper and words. Washington’s letter told Congress the Revolution might collapse for want of powder. The King’s speech drafts in London told Parliament that reconciliation was already dead. The soldiers in the trenches did not know the full truth, but they sensed it: the war had already moved past half measures.

Looking back, October 1 marks one of the quiet turning points of the Revolution. It was the day Washington confessed how fragile his army was. It was the day Congress faced the reality that passion alone could not keep the army alive. And it was the month in which Britain’s King resolved that rebellion, not reconciliation, was the future.

The Revolution survived October 1, but only barely. It survived on bluff, on Washington’s calm, on the hope that powder would be found, and on the illusion that a fragile army could hold the might of Britain at bay. It survived because both sides, across the Atlantic, still underestimated how long and bitter this war would become.

Leave a comment